-

Lødingen Pilot- and Telemuseum, 2016 Stein Domaas/Telemuseet

He meets us at the door. He’s leaning on a walking stick, his health has started failing, but his eyes are bright and the handshake firmer than most. Kyrre Bjugn is a veteran at Telenor, and one of the pensioners still on the company’s payroll. Today, he has driven the 500 meters from his home to show us the station and tell us about what was locally called the “Telegrapher’s paradise”.

At the beginning of the last century, Lødingen telegraph station was the main central for all tele-traffic in northern Norway. All telegrams from Bodø, Vadsø, Hammerfest, Tromsø and Vesterålen had to pass through this white timber building at Tjeldsund in Vestfjorden before being sent on. And we’re talking quite a number of messages: In 1917 over two million telegrams were sent from here. In old black and white photographs we can see corset-clad female telegraphists bent over polished Morse apparatus – like a snippet of refined society in the middle of the barren nature of the north. But how was it, working here at Lødingen? What role did the telegraph station play in village life? Is it correct that there were as many women as there were men working in the company?

- 1/2

Lødingen telegraph station Ukjent/Telemuseet - 2/2

Lødingen new telegraph building, after 1895 Ukjent/Telemuseet

-

Kyrre Bjugn Stein Domaas/Telemuseet

Kyrre tells us the story

Walking steadily, he shows us the way into the impressive Swiss chalet style villa. He has brought his own private archive; a red binder filled to within breaking point of anecdotes, reports, pictures and correspondence. Kyrre will fill the next four hours with detailed knowledge concerning the history of telegraphy in general and Lødingen Telegraph Station especially.

-What Kyrre doesn’t know, is not worth knowing, says Bjørnar Pedersen, manager of the station. He too has worked his entire lifetime for Telenor.

-Bjørnar is a blessed man, says Kyrre.

-For twenty years I waited for someone to take over after me. I’ll turn 89, and you see the state of my health. That’s when Bjørnar turned up. I’m so immensely fond of that man.

They have known each other for years. Ever since the time Bjørnar was sixteen and racing around Lødingen on a tuned-up moped. How did they meet? Bjørnar is smiling:

-We used to live here at Lødingen telegraph station at the same time, Kyrre with his family on the first floor and me in a flat in the loft. Kyrre counted 14 pairs of shoes outside my door, when I had the guys over once.

- 1/8

Entrance Stein Domaas/Telemuseet - 2/8

Main entrance Stein Domaas/Telemuseet - 3/8

Exterior, details Stein Domaas/Telemuseet - 4/8

Exterior, details Stein Domaas/Telemuseet - 5/8

Architect plan Stein Domaas/Telemuseet - 6/8

Interior Stein Domaas/Telemuseet - 7/8

Reception Pilot - and Telemuseum Stein Domaas/Telemuseet - 8/8

Stairs to first floor Stein Domaas/Telemuseet

-

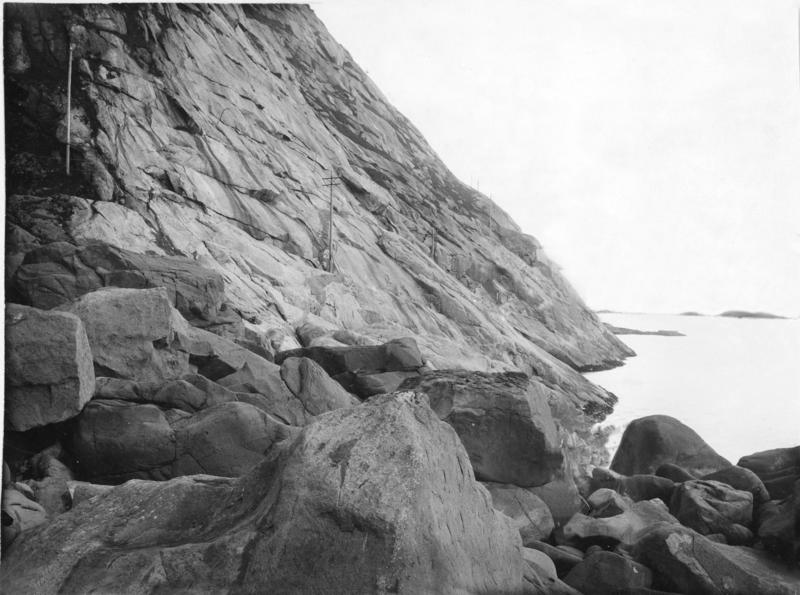

Lofoten telegraph line Ukjent/Telemuseet

It started with the Lofoten line…

Personal memories mix with the memories of Norwegian tele-history as we enter the building that has been housing the Pilot- and Tele museum since 1995. Half of the ground floor is dedicated to the pilot profession, and the rest displays the county’s tele-history. There’s a table covered in filled bread-rolls placed between the two exhibitions.

-Grab cups in the cupboard to the right, says Kyrre, as Bjørnar heads off to collect the dishes. The old-timer is properly at home here, and before we have finished the coffee he starts to recount:

-To understand the origins of Lødingen telegraph station, we have to start with the Lofoten line, he says.

-During the Lofoten fishery in 1859-60 it was calculated that having a telegraph line up here would increase the catch by 25 percent. Because a fisherman in the west of Lofoten had no way of knowing what was happening in the east of Lofoten and vice versa. This argument caught the imagination of the politicians, and funds were granted for a local telegraph line in Lofoten. In 1861, 170 kilometres of telegraph line was rigged in five months, from Brettesnes to Sørvågen.

While underway small telegraph stations were constructed in local fishing communities.

-170 kilometres in five months? These were industrious people!

-Sure, but the workmen hired from here in Lofoten disappeared after a few days, do you know why?

-No?

-They weren’t accustomed to regular wages. They were fishermen after all!

A local fisheries-baron and his pretty daughters

It’s exactly such detours that make listening to Kyrre great fun. To be truthful, the subject of telecommunications can be quite dull and hard to grasp. This is not the case when Kyrre tells the story. His enthusiasm is contagious and turns facts concerning technical and industrial cultural heritage into living history. To him this tale is about people and the conditions they lived under. And this is how the answer to why there is a telegraph station at Lødingen, can start with a local fisheries-baron and his pretty daughters:

-In 1868 the Lofoten line was connected to the main national network, and the first telegraph station established at Kjeøy. A herring fisherman by the name of Roness had a house, which had been brought here from Bergen (After the great city fire in Bergen, it was decided that all buildings there should be constructed out of bricks and mortar). It is uncertain why Telegrafvesenet decided to look for a new location, but after a few years at Kjeøy they started looking both east- and westward for new opportunities. At Offersøy in the west there lived a local fisheries-baron who apparently had some pretty daughters. He didn’t want any of these fancy telegraphists near his daughters, and so, therefore, the focus was moved eastward, to Lødingen. The telegraph station was established here in 1875.

-In this house?

-No, they hired premises from a local merchant who had established himself in the harbour area, Arentz Schøning

-

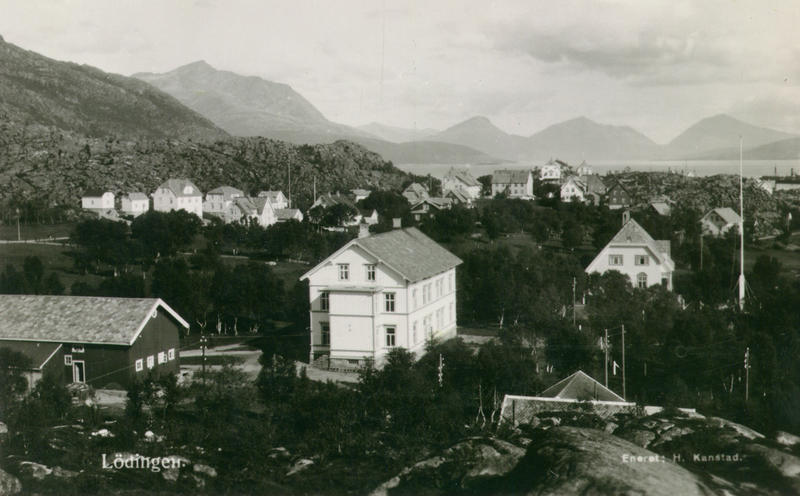

Lødingen telegraph and residence for the staff H. Kanstad

A local society emerges

The business grew, and the telegraph station soon needed premises of its own. After all, Lødingen had become the telegraph inspectorate of Northern-Norway, after inspector, Bødtker Lie moved here from Tromsø in 1875.

- Kyrre smiles contentedly, I usually say that Lødingen won and Tromsø lost.

In 1895 the new station was completed with two spacious floors plus loft and cellar. On the ground floor was the telegraph station with the reception, a Morse-hall, a Wheatstone-hall and a Siemens-hall. The inspector with family lived on the floor above while the loft contained flats for the employees.

-And there were outbuildings for the livestock across the yard, states Kyrre.

-They had animals?

-What d’you reckon? They needed milk!

Not only animals arrived at Lødingen. Despite gloomy predictions made by one of the first inspectors, (“This desolate and lonely place, surrounded by peatbogs and stony heathland is not very alluring to the young telegrapher”), the activities of the telegraph drew ever more professions to the village.

-Not very many lived here in 1865, just the priest, a tenant farmer and those belonging to the priest’s household. When Telenor (Televerket) arrived, there was a sudden need for tradesmen, and more; shoemakers, tailors, and masons, says Kyrre.

-So the telegraph station had become a cornerstone business?

-Yes, it was the key to the development of Lødingen.

-

Morse telegraphtransmitter, 1910 Cato Normann/Telemuseet

Industrious northerners

And what was the basis for the telegraph station? This all happened as a direct result of the development in telecommunications technology, which really accelerated in the middle of the 1800s. Samuel Morse developed the Morse apparatus in 1837, and in 1895 the Italian, Marconi invented wireless telegraphy. Northern-Norway was in no way behind, neither nationally nor internationally. The second wireless, civilian connection established in Northern-Europe was between Røst and Sørvågen in Lofoten in 1906, across the feared Moskestraumen (dangerous ocean current).

-A telegraph manager by the name of Øwre, wanted to see if it was possible to get a signal across this large span of water, and it was! However, they didn’t have a transmitter on the island of Røst, so someone had to row the 60 kilometres across to relay the message that the experiment had been successful. When the rower spotted people on the water on the other side, he got up in his boat and shouted: “We heard it! We heard it!”

Another example of future-minded northerners is to be found even further north, says Kyrre:

-The first telegram in the world was sent between Baltimore and Washington in 1844. Just 26 years later, in 1870, we had telegraph lines all the way to Vardø.

-So it didn’t take long for them to realise the value of telegraphy up here?

-No, and that’s when eternity commenced.

-What happened here must have seemed immensely new and exciting, says Bjørnar thoughtfully. As the manager of the exhibition, he is constantly reminded of the furious development in telecommunications- for instance when school-youth visit and have no understanding of why there are wires coming out of the telephones.

-I have often thought about those first telegraph lines, and about messages sent using a Morse-key. I partook in a large conference with scientists from all over the world in Tromsø in 1990-91. There were some Japanese attendees there who were going to test out something called “an internet connection” Using this; they could check their letter box back in Japan. It sounded completely strange. How on earth could they sit in Tromsø and look into a letter box in Japan? We didn’t understand. In all likelihood people would have had the same feeling when the first telegrams started ticking out of here.

-

Lødingen telegraph, 1890ties Ukjent/Telemuseet

“Prone to melancholy and hypochondria”

At one point Lødingen was number three when counting the number of telegrams sent in Norway. But, Kyrre, points out:

-This was mainly relay traffic. Because the signals from the northernmost lines didn’t reach further than Lødingen, they had to be redistributed from here.

-All the tele-communication that that took place in Northern-Norway had to go through this room, says Bjørnar, and nods his head towards the green painted chamber entitled “the Circus”. Up to 36 people worked here at any time. The room carries a patina of use. In several places the solid floorboards are pitted from heels of shoes being ground against it.

-And what was it like, working here?

-It was probably good, thinks Kyrre.

-Down in Oslo they were saying that the telegraphers here in Lødingen were; “prone to melancholy and hypochondria”. Well, Telegraph Inspector, Strømsted, arrived in 1896, and didn’t leave until 1931. Surely he couldn’t be prone to melancholy and hypochondria.

Kyrre points to a cardboard cut-out depicting a uniformed man with a sleek moustasch.

-By the way, he was a great personality up here. So the people down in Oslo can accuse us of being prone to melancholy and hypochondria, but one thing is certain; the history of the telegraph here at Lødingen is absolutely unique.

-What are you thinking about?

-The activity! Their inventiveness!

Like the time in 1904 when they needed to construct some cabins. They got the local youth about to undergo their confirmation to transport the materials in exchange for waffles and fruit squash. Or when three assistants were out picking cloudberries on a neighbouring island, but lost their boat and had to spend the night out in the pouring rain. Or all the gossip produced by “the story of the cumbersome stove”, elaborately described in the correspondence between the canteen committee and the landlord, Schøning – correspondence which, of course, is preserved by Kyrre

-And if they had nothing else to do, they would practice with the Morse-key. It was said that one could tell if a telegraphist had been posted to Lødingen. They kept a particular beat when tapping out messages.

In time, Lødingen became a place where all young telegraphers did well to pass through. The stay would produce good references, says Kyrre.

-It does look quite grand in these old pictures?

-Yes, this was probably quite a posh place, thinks Bjørnar.

-If you were in the employment of Telegrafværket, you were seen as a professional. You really were someone, agrees Kyrre, not least because you were a state employee. This meant job security.

-Wasn’t it seen as a bit snobbish, this place? Bjørnar looks quizzically to Kyrre.

-They held classy garden parties in the park, where they even played cricket?

-Yes, it probably was, admits Kyrre.

-But that sort of thing was over when we arrived here. I’m of working class stock anyway, none of that causes me any grief.

-

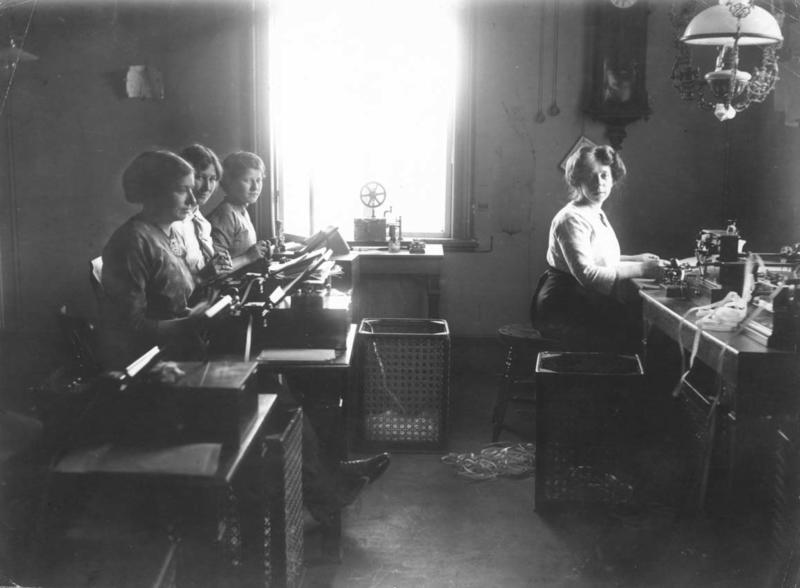

Female employees at Lødingen, 1900 Ukjent/Telemuseet

Women in the workplace

The daughter of Telegraph Inspector, Strømsted, the man behind the cardboard cut-out in the exhibition, was her father’s equal when it came to gruff authority. With a steady gaze and rolled-up sleeves, the young telegraphist is reminiscent of the English suffragettes. Kyrre confirms that, yes; Telenor (Det Norske Telegrafvæsen) was one of the first workplaces to hire women:

-Norway’s first four telegraphists, engaged in 1854, were officials who had undergone the telegrapher training. Later, two women were employed towards the end of the 1850s. At Lødingen, the staff consisted almost only of women, says Kyrre.

The first women to be hired by Telenor (Den Norske Statstelegraf) were the sisters, Nielsine and Martine Breda from Kristiansand. They enter the story in 1858. Telenor was early on an important employer of women, but should not shout too loudly about the company’s innovative policies on equal rights. In a letter to the ministry, the Director General of the telegraph, Carsten Tank Nielsen, writes: “The female telegraphists would be adequately satisfied with a lower wage than that of their male counterparts.”

Kyrre joined the company by coincidence. As the son of a fisherman from Bø in the outer reaches of Vesterålen it was not granted that he would end up in Telenor, but in 1949-50 he did the “ordinary training” in Kirkegata 9, Oslo. After a few years climbing telephone poles in Finnmark, he ended up in an administrative position at Lødingen in 1963.

-I went straight into an awfully interesting case concerning property, he says enthusiastically. A leased plot was to be returned from Telenor (Telegrafværket) back to the ownership of the Church, a process involving a complicated survey of property and borderlines.

-We didn’t close the case until sometime in the 70s, he says.

-And every time I had any questions, I would look through the books. I always found more than I was looking for.

The interest in telecommunications history started then, and as time went by, it was Kyrre that people came to with questions concerning all sorts, from the telegraph station to genealogy and local society. What information Kyrre doesn’t carry around in his head, he can find in the books that are neatly stacked in the office that is still to his disposal up in the loft space. Here are boxes upon boxes of documents and papers, gathered throughout a long life.

-

From exhibition at Lødingen Pilot - and Telemuseum Stein Domaas/Telemuseet

The end of the telegraph station

1936 saw the end of activity in the old station due to the classic story of new technology making old occupations redundant. We are starting to get used to this effect by now, but for Lødingen in 1930, it meant catastrophe.

-New technology made it possible to send telegrams over greater distances. You could send from Tromsø to Trondheim, from Hammerfest to Trondheim, from Svolvær to Trondheim, there was no longer need for the redistribution services offered by Lødingen. Because of this the requirement for people dropped, says Kyrre

-Telegraph manager Kjeldsø who also sat in the local council, wrote a complaint against Telegrafvæsenet: How can they tear apart this society? People have built houses for themselves, and acquired mortgages. What are they supposed to live off when their jobs disappear?

But the future was unstoppable. Not only was it possible to send telegrams over greater distances, but people were about to stop sending telegrams altogether. The telephone was taking over. The remaining activity was moved to Lødingen station- and administration building, also called “Messa”, while the old station became living quarters for the employees. Among them we find Kyrre and his large family. Bjørnar lived here as well due to his father working in Televerket. A new room plan and wallpapered plasterboard walls turned the house from workplace to home, and that’s how it stayed up until the 90s when Telenor decided to renovate the station and restore it back to its original elegance.

-That’s when they found this beautiful skirting, says Kyrre, and points his stick towards some broad, carved boards running along the base of the wall.

-They also revealed the original panelling. It did of course cost a bit of money, but if they hadn’t done it then, it would never have been done.

His gaze travels around the room. It’s filled with artefacts of a different time, and a profession that no longer exists. Kyrre knows that all things perish in time, and that a story has to be told to be kept alive. Only then can we learn from the past. The old man grabs his stick, he has done his bit.

- 1/2

From exhibition Stein Domaas/Telemuseet - 2/2

From exhibition Stein Domaas/Telemuseet

- Bjugn, Kyrre "Telehistorikk fra Lødingen" Lødingen Association for Local History

- Historic lines- Protection plan for Telenor’s buildings and intallations Url: http://telemuseet.no/utstillinger/lodingen/

- Url: http://www.aftenposten.no/norge/Teleeventyret-startet-i-Lofoten-407501b.html

- Url: http://www.lofoten-info.no/telemuseum/