In the center of history

When Telenor developed a plan for the protection of its buildings and technical installations in 1997, there was never any doubt as to whether the telegraph station in Ny-Ålesund should be on the list. Throughout many years, the blue house was the lifeblood of one of the world’s northernmost human settlements, and the only possibility for its inhabitants to stay in contact with the mainland through long and isolated winters. A lot has happened since those days. Today Ny-Ålesund is a high-tech centre for arctic research and for monitoring the environment. Listening for noise from black holes 31 billion light years away, is one of the projects the scientists are currently engaged in. That’s why it’s important to turn off Wi Fi and mobile phones on arrival to Ny-Ålesund, in order to prevent any disturbances to the sensitive listening equipment.

We are about to go back to a time when 4G didn’t exist, and the only wireless communication happening in Ny-Ålesund went through this particular blue-painted telegraph station. Let us start with the beginning.

- 1/1

Restoration completed Laila Andersen/Telenor Kulturarv

- 1/2

View from Ny-Ålesund Laila Andersen/Telemuseet - 2/2

Radiotelegrafistasjonen i Ny-Ålesund, 2016 Stein Domaas/Telemuseet

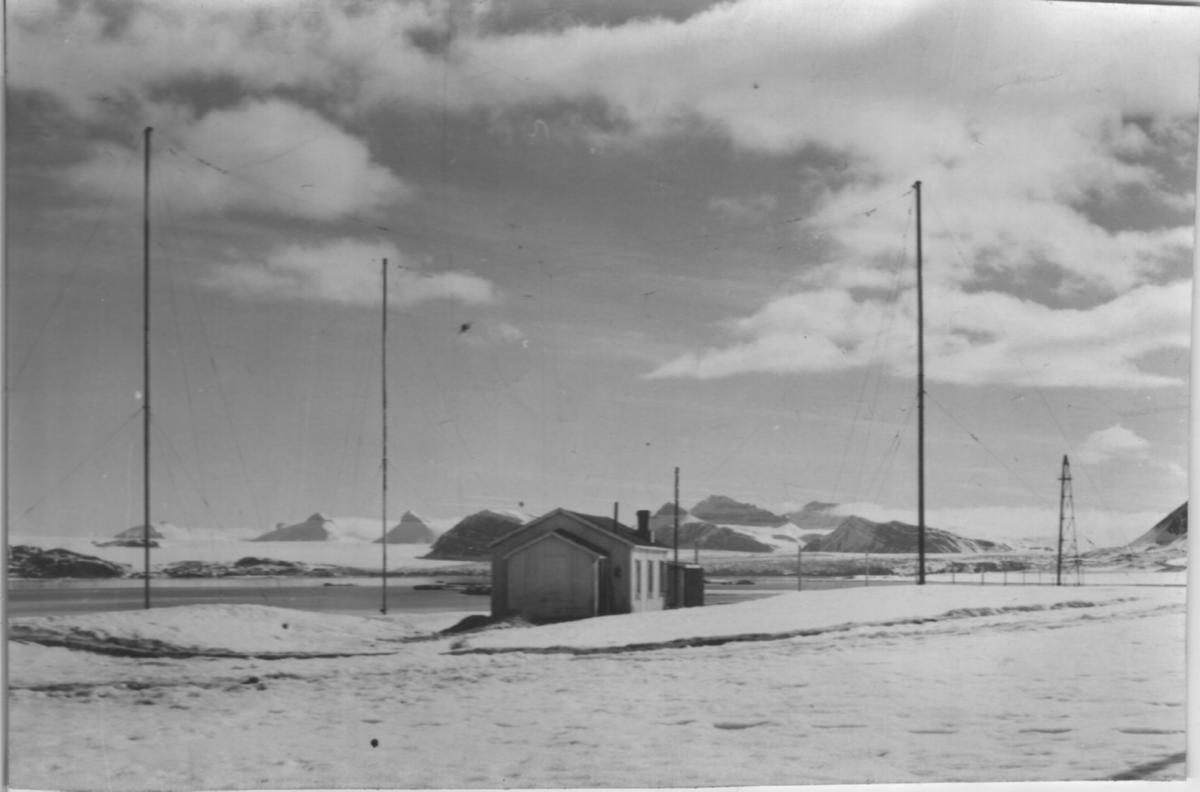

Radiotelegraph building at Ny-Ålesund Ukjent/Telemuseet

Establishing a telegraph station

Who decided to build a telegraph station exactly here, on 79 degrees north, and why? The answer lies deep within the mountain, in the coal mines. The black gold tempted Norwegians and Russians alike to establish industry on Svalbard in the beginning of the 20th century. In 1916 the state owned Kings Bay Kullkompani (Coal Company) was founded and started mining operations in Ny-Ålesund. Just two years later, the place got its own telegraph station. This made business here more efficient but there was also a question of safety. The decision to build a telegraph station came a couple of months after the mine’s manager and two of his men had to walk for 44 hours in order to bring news of that winter’s coal production to Longyearbyen. They spent a night in 42 degrees below zero, the dogs ran off with all their provisions and one of the men ended up having to amputate all the toes on one foot.

VG (national newspaper) announced the news about the new telegraph station under the headline: “Our wireless rule over the icy seas”. The decision to establish this wireless infrastructure on Svalbard turned out to produce big politics. 7 years earlier the Parliament had on the initiative of director, Thomas Heftye in Telenor (Norges Telegrafvæsen), decided to build Spitsbergen Radio at Finneset in Grønnfjord. In those days, installing such high-tech equipment at Spitsbergen was an enormous investment for poor Norway, but may have been decisive in granting the country’s sovereignty over the archipelago in 1925.

To the standard of the day, the new telegraph station in Ny-Ålesund was fitted out with top modern equipment, like Wheatstone-Morse apparatus. The little mining town had gained a communications hub. In places where people meet and conversations take place, things often start to happen; important events were afoot at the telegraph station.

- 1/5

Radiotelegraph building 1996 before restoration Egil Reimers/Telemuseet - 2/5

Exterior in need of restoration Egil Reimers/Telemuseet - 3/5

Details of decay Egil Reimers/Telemuseet - 4/5

Interior previous to restoration Egil Reimers/Telemuseet - 5/5

Interiør med sikringsskap før restaurering Egil Reimers/Telemuseet

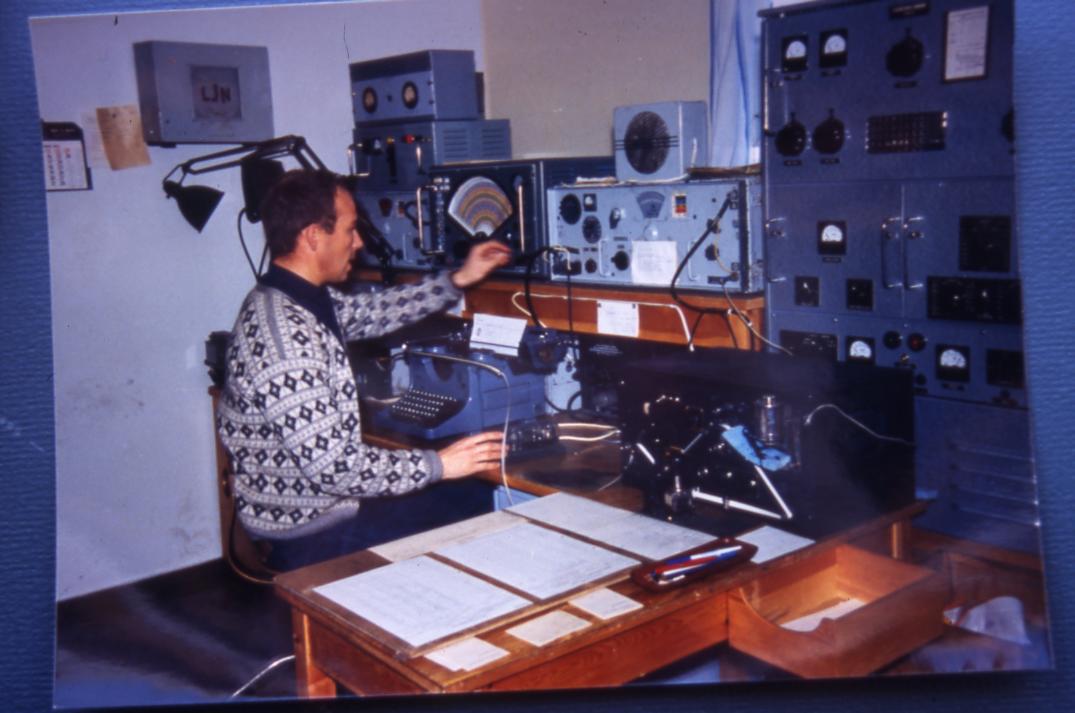

The operators desk Ukjent/Telemuseet

The exploits of Roald Amundsen

Situated halfway between Norway and the North Pole, Svalbard became a natural stop as Roald Amundsen got ready to reach the North Pole in an airship. “I have never been closer to the centre of the world, and never will be again,” wrote telegraphist, Odd Sandvei about his experiences in the spring of 1926. He was on duty as Amundsen left Ny-Ålesund in the airship, “Norge”. For a few hectic weeks the whole world was watching. With the Italian, Umberto Nobile, Amundsen had planned to be the first to cross the North Pole, and international media was excitedly awaiting news. In an internal magazine for the telegraph company, Verk og Virke, Sandvei describes how the press was keeping the telegraphers busy with long reports on weather, wind and the midnight sun, when no news arrived from the polar explorers.

The story of Roald Amundsen and the telegraph station in Ny-Ålesund might have ended here, but instead carried on to reach a far more tragic finale. In 1928 the polar explorer assisted in the search for his former partner, Nobile. After a heavy argument, Nobile decided to make another attempt at crossing the North Pole, this time in the airship, “Italia”. When “Italia” disappeared in the icy wastes, Amundsen flew out to look for his arch enemy. His airplane crashed somewhere near Bjørnøya. The last life signs coming from Roald Amundsen were received by the telegraph station in Ny-Ålesund.

Operator at work in the 1960ties Ukjent/Telemuseet

The Kings Bay accident

The autumn of 1929 saw the temporary end to mining in Ny-Ålesund. The coal prices were fluctuating, and for the next ten years the telegraph station was only up and running in the summer, during tourist season. Then came the war and put a stop to all activity on Svalbard. In 1946 telegraph services were reopened, and the station relocated to a more centrally placed building in the centre of Ny-Ålesund. In the following years the telegraphists’ work was mainly related to the mining. In the beginning of the1960s just over 150 people worked in the mines, additionally, there were wives and around 20 children living in the little town. But mining is a perilous profession, and Kings Bay was little by little turning into the most dangerous workplace in Norway. Throughout the 1940s and 50s over 40 employees were killed in work related accidents.

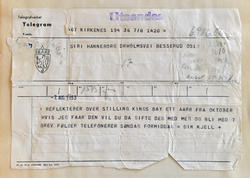

Isfjord Radio. Isfjord Radio. Ny-Aalesund Radio calling. I have an express message for Norway. Mine explosion on the 5/11 at 22.45 in belt-shaft west claimed18 possibly 20 human lives stop cause of explosion unknown STOP

When telegraphist Jo Hammer late at night sent the message about the horrible event, he could not know that it would lead to a crisis in government. The public opinion was forceful, and the press did not let up the pressure; someone would have to take responsibility for the lost lives. Seeing as Kings Bay was a state owned company, the affair ended with Prime Minister, Einar Gerhardsen, and his men having to leave office.

- 1/2

Proposal by telegram - 2/2

Accept of proposal

Exhibition of original equipment from Ny-Ålesund radiotelegraph Stein Domaas/Telemuseet

Restauration and exhibition

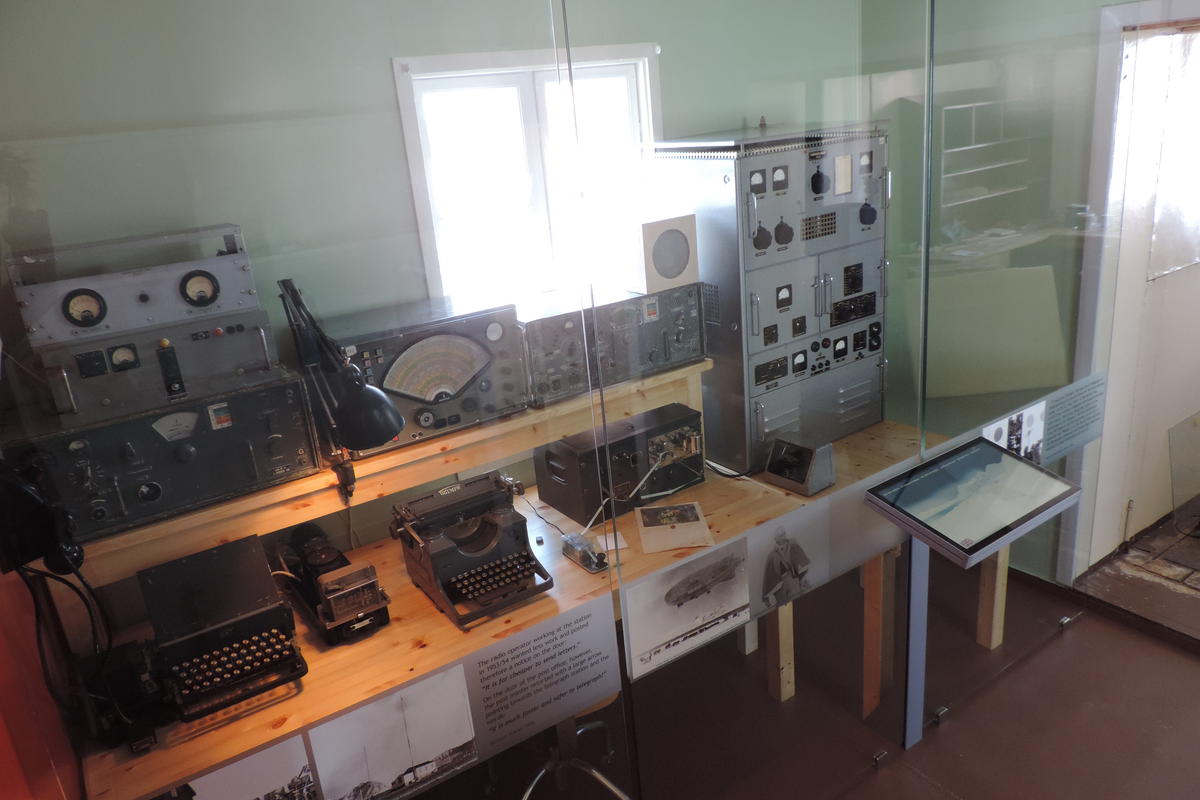

The tragic accident led to a final stop to all mining in Ny-Ålesund. And so there was no longer need for a telegraph station, and the house with the dramatic history was left to decay. In 2014, however, the station was restored in collaboration between Kings Bay, the Directorate for Cultural Heritage, the Norwegian Telecom Museum and Telenor. The interior has been returned to the way it was in the 1960s, and the station’s original equipment has been brought “home” from the Norwegian Telecom Museum’s storage rooms in Fetsund. It is now safely housed behind glass walls, as part of the Telegraph Station’s exhibition. Those interested can take a closer look at tele technical artefacts like: A line amplifier manufactured by Televerket’s main workshop, Lorentz shortwave- and longwave receivers dating from World War II, a Wheatstone-machine transmitter for Morse-signals, a Siemens communications receiver from the 1950s, a Telefunken loudspeaker, a Morse tele printer from the US Army Signal Corp., an EB-radio transmitter type 13-SS-300, a line changer from Elektrisk Bureau, a voice distortion unit and a Morse key.

- 1/4

From entrance Stein Domaas/Telemuseet - 2/4

Norwegian Minister of justice visiting the new exhibition Stein Domaas/Telemuseet - 3/4

Radiooperators equipment from Ny-Ålesund Stein Domaas/Telemuseet - 4/4

Interior restored Stein Domaas/Telenor Kulturarv

Sources

- The Telegraph Station’s own web page. http://www.telegrafstasjonen.com .

- Amundsen, Roald. Store Norske Leksikon (Norwegian Encyclopedia).. https://snl.no/Roald_Amundsen (2016, august, 25).

- . http://svalbardmuseum.no/forskning/amundsen-og-nobile/ .

- . https://no.wikipedia.org/wiki/Umberto_Nobile .

- . https://www.nrk.no/troms/pusset-opp-historisk-telegrafbygg-1.11740084 .