Mottakerstasjonen på Skjæveland. Ca. 1983 Ukjent/Telemuseet

The receiver station

In 1960 the world’s most advanced short-wave radio station opened at Skjæveland, Sandnes. At this point Rogaland Radio took over as the national short-wave station after Bergen Radio. At its peak more than half a million telegrams were sent from here every year. The Telenor veteran, Egil Reimers remembers the work environment at the receiver station as particularly good.

- 1/2

Receiver hall, 1974 Ukjent/Telemuseet - 2/2

Telex room, 1974 Ukjent/Telemuseet

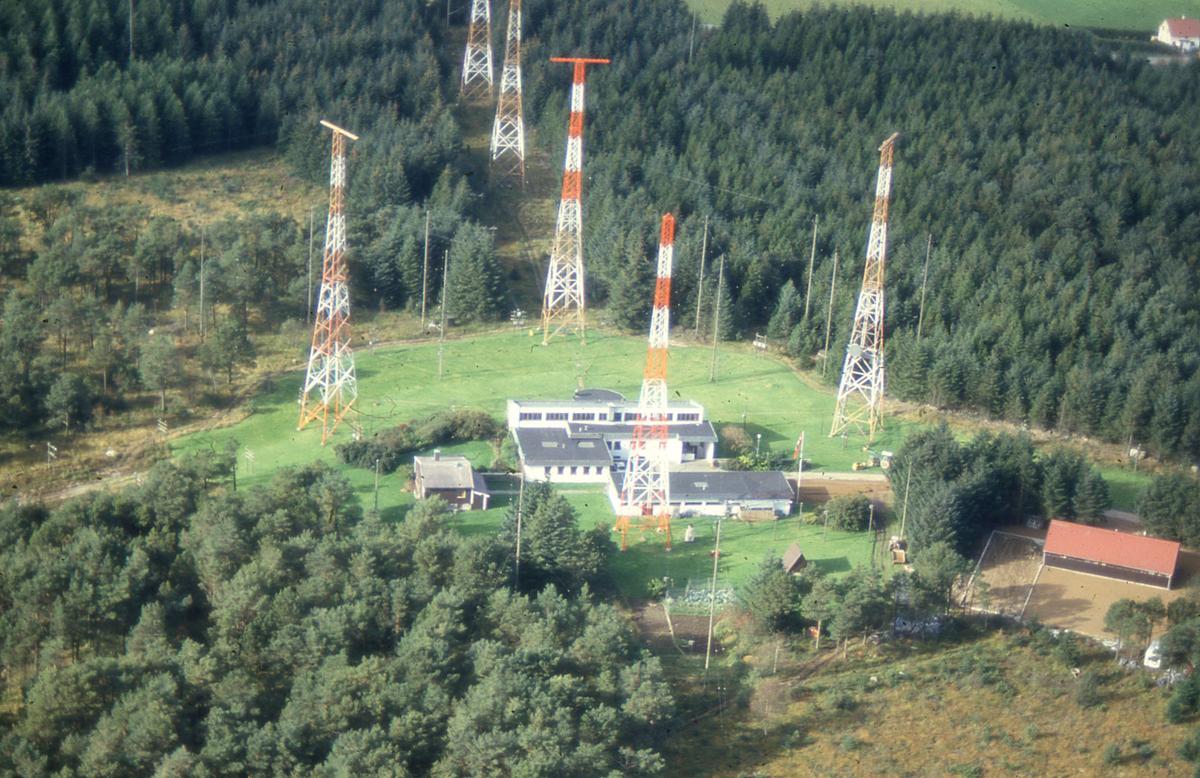

Senderstasjonen for Rogaland radio i Vigreskogen, 1970-årene Ukjent/Telemuseet

The transmitter station

Rogaland Radio’s transmitter station is a 600 sq. metre building in the Vigre forest, 20 kilometres away from the receiver station. The distance was meant to stop disturbances to the reception caused by its own transmitters. At the most 10-12 people worked at the transmitter station in looking after the 30 transmitters.

- 1/2

Transmitter station at Vigreskogen, 2016 Stein Domaas/Telemuseet - 2/2

Transmitter station Stein Domaas/Telemuseet

Master ved Skjæveland, Rogaland radios mottakerstasjon, 2016 Stein Domaas/Telemuseet

The receiver masts

At 20 metres high, they are very visible in the flat Jæren landscape. At Skjæveland in Sandes 30 wooden masts stand in formation, equipped with directional antennas for short-wave reception. With these, Rogaland Radio could receive signals from vessels out on all the world’s oceans.

Mastene i Vigreskogen, Rogaland radios senderstasjon, 2016 Stein Domaas/Telemuseet

The transmitter masts

In the Vigre forest in the municipality of Hå, 10 mighty masts are placed in a triangular formation. The 50 metre steel towers were erected in 1959, and once carried an array of advanced directional antennas for short-wave transmission. Messages from Rogaland radio were sent via these to Norwegian ships all over the world.

Egil Reimers (left) visits Skjæveland, 1999 Cato Normann/Telemuseet

Egil Reimers about Rogaland radio

He is probably the one person who knows the most about Rogaland radio. Egil Reimers spent three periods at the coastal radio station during his 40 year working in Telenor. He came here the first time when the station was only half a year old. By a coincidence the young radio telegrapher from Rogaland ended up as a summer substitute on the service desk. In 1963 he stopped by again for a year, before he became the HR manager and deputy manager in 1973. In 1983 he left Rogaland Radio for good.

Some places make such deep impressions in us that we never really leave them. Egil Reimers must have left a little of his heart at Rogaland Radio. With great enthusiasm he tells the story of his old work place, one of the world’s largest and most advanced short-wave radio stations for maritime telephone- and telegram traffic. This story is mainly about a particularly good work environment and technology passed its due date, but first and foremost it’s about an important epoch in telecommunication history.

For the telegraphers out at sea, Rogaland Radio was “next to God,” and many had an enormous respect.

Ekspedisjonsplass ved Rogaland radio, 1974 Ukjent/Telemuseet

The heyday

The Norwegian fleet was probably at its all- time peak, when Rogaland Radio was established, begins Egil.

-We were still in possession of a fair few whale boiling facilities, which in one way was the oil industry of its time. They were stationed down in the Southern Ocean from September to April, often with 300-400 men connected to each boiling operation. There were about ten of these, and they had no other way of contacting their homes and owners than the short-wave, mainly sending telegrams. They would create so much traffic that an operator would sit through an entire shift receiving and sending telegrams from one boiling facility.

-Was Rogaland Radio meant to only keep in contact with Norwegian vessels?

-Well, it was established for the benefit of the Norwegian fleet, but like any western station Rogaland Radio would receive traffic from any ship that called up. Traffic from other Scandinavian countries increased especially when radio telephony got into full swing, with all those directional antennas. Little by little, other countries also started using Rogaland Radio for their communications because it delivered the best results.

-Was it because of the technology that the signals were so good?

-It was a mixture of good technology and great service from the personnel. Rogaland Radio had a flexible service desk, which efficiently moved the traffic through. They were very highly regarded by the ship’s telegraphists due to their extremely high competence level. Practically all of them had experienced life out at sea, so they were very service minded towards the seafarers.

-So they had been out to sea themselves?

-That was pretty much a prerequisite to get a job at Rogaland Radio. Almost all the personnel on the Service desk were former ship’s telegraphists, me included.

-So you knew the conditions the seamen lived under, and you spoke the “lingo?”

-Yes, and I suppose that’s the way Rogaland Radio became known for their good service. We had a deeper understanding of life at sea compared to those telegraphists who had maybe only seen a boat, but never been on one. We would practically get in the mind-sets of those who were out at sea, and those few of us, who hadn’t been sailors, were quickly permeated by the environment, or christened, so to speak.

He laughs quietly:

-For the telegraphers out at sea, Rogaland Radio was “next to God,” and many had an enormous respect.

Many of the ship’s telegraphers got summer employment at Rogaland Radio, including Egil. That happened in 1961. 25 years old he turned up outside the brand new radio building asking if he could take a look.

-I had no idea I would be offered a job that day, he smiles.

-But after I had been taken on a tour, the manager on duty came over and asked me if I would consider a position as a summer substitute. And so I got a job, completely by coincidence and to my great surprise. I have to admit that when I sat down that first day, I felt like a beginner, even if I did have some years of experience. It was exciting with all that new and fantastic equipment they had. Everything was so great, it was a pleasure.

Receiver hall, 1974 Ukjent/Telemuseet

The quietest hall

All the receivers had choices of directional antennas to achieve the best possible signal. The location in the flat geography of Jæren was also a factor in optimizing the conditions. The intention was to place the transmitter station at Flesland, but then the Parliament decided to use that plot for an airport. After thorough research it was decided to establish the new transmitter station for the short-wave service at Vigre in the municipality of Hå. Due to the powerful transmitters, the receiving station had to be placed at least 20 kilometres away, and in 1960, the new receiver station at Skjæveland in Sandnes was opened.

-It’s not strange that you felt a bit awed on your first work day at Skjæveland. Pictures in the Norwegian Telecom Museum’s archive show an enormous hall, with lots of service desks lined up.

-The peculiar thing about the great receiver hall for Morse telegraphy, was that it was completely silent, tells Egil.

-All you’d hear was the sound of the conveyor belts transporting telegrams from distribution and out to our positions. Everyone sat there with their headphones on, tapping away at a type writer. Morse code came with a limit of 100 signs per minute, so it wasn’t exactly speed typing either, he says and laughs softly:

-Around Christmas time, journalists from Stavanger Aftenblad and other newspapers would come to visit. They had been told that the place was “boiling” with activity.

-Due to all the seamen coming home for Christmas?

Yes, up to 1975 the Christmas traffic was enormous. In the daytime no chair would ever get cold, and you would have to have personnel ready to step in when someone went to lunch. When the journalists entered the telegraphy hall, however, people just sat there and looked into space, while the typewriters went click click clack. It didn’t seem particularly “boiling,” he smiles.

-Of course there were the odd outbursts. Not all the telegraphists at sea were equally easy to operate against. Some had to give air to their feelings afterwards, he laughs.

Tecnidal equipment, Skjæveland, 1999 Cato Normann/Telemuseet

Medico service and emergency signals

There must have been a bit of action every now and then? With the Medico-service Rogaland Radio put doctor and ship in contact if someone out at sea got ill or hurt in an accident. On rare occasions even surgery was executed over the Medico. Were there times when temperatures ran high at work?

-Yes, I suppose so, but that was mainly to do with the amount of traffic, says Egil.

-Among 20 telegraphers, top priority is of course given to the one who’s handling the Medico service. That traffic came before everything else, and of course, the person dealing with the communication to and from the ship that needed medical help, did probably have a particularly exciting shift. It was often mentioned in the canteen afterwards, even if there wasn’t too much talk about it.

-It almost sounds like a news desk, where messages are ticking in to be dealt with as quickly as possible.

-Yes it was important to get things moving, he nods.

For this purpose they had systems. Egil recounts:

-For all the ships that were regular customers we had a card on which we made notes during contact with that ship. The cards were all sorted by call sign, and the messages were filed in an A5 folder. When traffic was particularly great, there would be a man on each bandwidth. We’re not going too far into the technicalities here, but service was given on different bandwidths. Then there would be one man per bandwidth listening for calls from the vessels and taking notes of what frequency the vessels were on. They would then get the corresponding cards ready. The cards were then placed on the service desk in front of him, so that the others could come and pick them up. The oldest calls would be placed on top, unless there was something extraordinary, and then the cards would go out one after the other, and be serviced. When there was a metre or two of cards waiting it could get a bit hectic.

He chuckles:

-And then there were some that worked as if their life depended on it, while others were more inclined to take it a bit easier. But that’s how it is everywhere.

-And if an emergency call came through, that would come before everything?

-Yes of course. We rarely received an emergency signal on the short-wave; it was normally the coastal radio department that got them. When it happened it was of course extremely hectic. This was for instance the case during the major accident involving the express boat, Sleipner, which ran aground in the Haugesund area in November 1999. Not to mention the disaster concerning the oil platform, “Alexander L. Kielland” in 1980. It was handled by Rogaland Radio in communications terms.

Telex at Skjæveland Cato Normann/Telemuseet

Oil boom and teleprinters

Speaking of oil, the fact that the oil business took off in Stavanger in 1966 led to increased traffic for Rogaland Radio?

-Yes the oil industry generated a lot of traffic, and it led to an enormous rush, both concerning technical- and service issues. Especially during the first ten year period, up to approx. 1975, when Eik earth station was established, and the first oil companies received satellite communication.

- At Rogaland Radio it was Morse telegraphy which was the most sought after service?

- In the beginning, absolutely. There were 25 service desks for Morse telegraphy and 4 dedicated to short-wave telephony. Additionally, there was one for coastal radio. This tells you something about the priorities, he says.

-And you had something called a “teleprinter.” Could you explain a bit more about that?

He hesitates for a moment. To explain old telecom technology to today’s mobile phone generation requires a considered approach. Egil begins:

-The telegrams coming in from the ships would be received as Morse signals, which the operator in turn wrote down sign by sign on a telegram form. This form would then be sent over to the teleprinter department, also called the telex department. From there the message went out to the addressee’s nearest telegraph station. If, for instance, the addressee was situated in Rogaland, the message would first be sent to Stavanger before being called over to one of the telephone stations out in the villages. Here the telegram would be written down by hand and delivered to the correct recipient. Seafarers often came from Norway’s rural districts, innermost in the fjords and out on the islands, so they weren’t the easiest places to get to.

As early as in 1964, Rogaland Radio started sending and receiving telegrams directly to and from the big ship owners, tells Egil.

-Teleprinters are set up in a network in the same way as telephones. This meant that you could call up a telex subscriber and communicate directly, without going through a tele operator.

- 1/2

Telex Cato Normann/Telemuseet - 2/2

Telex Cato Normann/Telemuseet

Operators at Skjæveland, 1974 Ukjent/Telemuseet

Masts, sunspots and time zones

The antennas were crucial to Rogaland Radio’s status as one of the world’s most efficient coastal radios. When they were installed in 1959 they were hi-tech. With dipolar carpet antennas for the short-wave transmitters and rhombic antennas for reception, Rogaland Radio could reach all the world’s oceans.

-In principle we could, comments Egil.

-When I say “in principle” it is because short-wave communication is quite complicated. It varies throughout the day, with the seasons, if there is a lot of sunspot activity, the northern lights and so on. You almost never know when you will have a connection, but if you do, the quality can be very good even with simple means.

-But the equipment installed at Rogaland Radio increased the chances for high quality communication?

-The fact that we were equipped with directional antennas was in many cases crucial to being able to service a vessel.

Did the operators need to know a few things about weather conditions too?

He pauses for a moment:

Well…When you are working all day, every day, sending and receiving signals year round, you soon get a considerable experience, also in relation to time zones. The vessels would follow the time zone they were in. The zones eastwards, Japan, Singapore and the Persian Gulf, would generally be received in the morning time. When we passed mid-day they had mostly gone to bed. Then the western hemisphere would take over with the Caribbean and the east coast of the USA.

-And this is obviously why Rogaland Radio was staffed 24/7?

-Yes, but there were fewer staff in the night time. When I finished in 1983, the manager on duty would be concerned if we didn’t have 40 men for the morning- and afternoon shifts. At night we could be down to 15-20 staff.

Operators screen, Skjæveland Cato Normann/Telemuseet

The end of an era

In 1983 Rogaland Radio was at its peak with regards to the number of personnel, with approx. 180 employees, but with satellite communication via INMARSAT and the automated mobile telephone service (NMT) from 1981, the downturn had already started.

-We noticed that traffic started slowing down, remembers Egil.

From 1963 to 1994 the number of sent telegrams sank from 538.000 to 25.000.

-Morse telegraphy was formally closed down as a communicational system on the 1 February 1999 by the International Telecommunications Union (ITU). At this point it was no longer a requirement to have Morse-proficient personnel aboard ships. Telenor kept the service going for another year and a half, but then there were no reasons to keep it going anymore. The ships stopped using Morse sooner than expected.

The history of short-wave technology was much the same, he says, and continues:

-Not only was the technology moving on, there were also fewer and fewer Norwegian seafarers. When only the captain and the head engineer are Norwegians, there’s not much need for calling Norway.

The receiver station stopped operations in 2004 and was merged with the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre for Southern Norway at Sola.

-Was that a difficult time for the employees?

-Not really. After 1983 practically no new telegraphists/operators were employed at Rogaland Radio. Also a lot of staff left for natural reasons. Traditionally, telegraphists had the right to retire at the age of 62, and most took advantage of that privilege. They never got particularly old in that job anyways, he chuckles.

Wooden mast pole, Skjæveland, 1999 Stein Domaas/Telemuseet

Nothing but a memory

Today, what was the old place of work for Egil Reimers and so many other telegraphists and technicians is nothing but a memory.

-It’s a bit sad of course, but at the same time it’s just part of a natural development, he says. Egil played a part when Rogaland Radio was served a protection order in 1997 through the protection plan for Telenor’s buildings and installations. It wasn’t just the architect designed, modernist receiver station that was protected, but also the transmitter station and the huge masts. They have become landmarks in the Vigre Forest and at Skjæveland. Egil has not noticed any controversy regarding this.

-I actually believe the masts are seen as an attractive addition to the landscape. Personally I can’t see them spoiling anything, and they have after all served us well.

It was he who suggested that the masts were included in the protection plan.

-I had thought that they would have stayed in use a lot longer, but I nevertheless think it’s great that Telenor is taking its responsibilities seriously, and look after these things. They are an essential part of history.

Finally, a little grumble from a telecom-veteran:

-I sometimes feel that Telecommunication and its importance for the development of society is given too small a role in general history. We can all see how telecommunications is being used today. It seems like people have an inexhaustible need for communication. How useful it all is, I don’t know, but people clearly love to communicate.

He could have retired a long time ago, but Egil Reimers is one of those people who never stop working. There is no doubt as to where he belongs.

-When I retired, formally speaking, it was 20 years since I left Rogaland Radio. Still, that’s where I feel at home. I still go to Rogaland Radio’s pensioner meetings.

-So that’s where you belong?

-That’s where I come “home.”